March 13, 2007

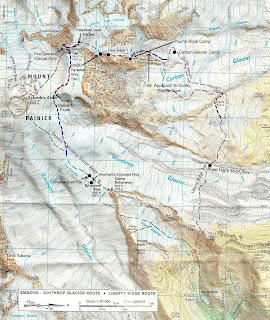

Edge of the Winthrop Glacier (+/- 7,200 Feet) to Carbon Glacier Camp (8,600 Feet), via Lower Curtis Ridge (7,200 Feet)

After a short nap, the horizon starts to get light, and we’re finally able to see the trail that had eluded us in the dark, only a hundred yards or so away from where we paused for a rest. We head out again, and while it's definitely getting lighter out, we’re still hiking in near - whiteout conditions, and we can’t figure out exactly where we are in relation to the beginning of our route.

Hooman in the Clouds

After another hour of hiking and more confusion about our position on the mountain, the clouds finally begin to open up for a few seconds every now and then.

Dan in Front of Willis Wall on Curtis Ridge

These brief moments of visibility finally let us determine exactly where we are, and we decide that in order to reach Curtis Ridge, and eventually the Carbon glacier, we need to continue across the snow slopes that we have been on after leaving the Winthrop Glacier.

Dan and Hooman, Willis Wall

Finally, after more cloud-induced hide and seek with the mountain, we reach Curtis Ridge, and are abruptly stopped in our tracks by a 200+ foot sheer drop down to the surface of the Carbon Glacier, the last obstacle in the approach to the actual climb on Liberty Ridge.

Liberty Ridge Route

After a bit of scouting past a couple of ridge-top campsites with dynamite tent sites and absolutely astounding views of the Willis and Liberty Walls, bisected by Liberty Ridge, we find a route down to the Carbon Glacier, rope up, put on our crampons, and start our trip across the violently crevassed, nerve wracking trek across the Carbon Glacier. We reach the first of the major icefalls on the Carbon, to be greeted by 100+ foot crevasses on all sides, with enormous seracs directly to our right and left, several of which collapse while we are in the icefall.

Icefall on Carbon Glacier

A quick, blood-pressure raising jaunt up this icefall takes us up and over a thin, steep patch of snow, around some truly frightening crevasses, all of which are bordered on either side by more huge areas of overhanging seracs.

Seracs on Carbon Glacier

A bit of zigging and zagging to avoid more crevasses, and we finally end up on a slightly less steep patch of snow, and continue up the glacier. After another 300+ feet of climbing, we are getting close to the base of Liberty Ridge, and the glacier starts to flatten out.

Dan, Hooman on Upper Carbon Glacier

At this point, it’s about 11:00 in the morning, and Hooman suggests that we again wait until dark to start the ascent of the actual ridge, to minimize the rockfall/icefall hazards we’ll be facing, so we find a semi-flat spot on the glacier, put down our tent rain fly, get out the sleeping bags, and start to melt snow for water. We all eat some food, sort gear, and just generally try and relax.

Fearless Visitor

Dan builds an excellent tiny windbreak wall to protect the stove while we melt snow, and we are visited by a fearless LBB (little brown bird), who apparently finds all sorts of interesting things to eat and/or peck at around our campsite, at times only inches away from our sleeping bags.

Dan's Cooking Wall

While we are lying here napping at this campsite, I make the unpleasant discovery that the shell fabric of my new sleeping bag is extremely slippery, and the spot that I picked for our campsite is slightly tilted. The combination of these two factors means that despite the ridges on closed-cell foam sleeping pad, when I am in my sleeping bag, even lying perfectly still, I will slowly creep downhill until I slide off my sleeping pad, off the tarp and into the snow at my feet, which, of course, will eventually melt and get the down insulation in the foot of my bag wet.

View from Campsite

Unfortunately, there’s not really all that much I can do about this phenomenon, so after much swearing at myself for picking a campsite on a hill, I just grit my teeth, and continually haul my pissed-off self back up the hill onto the sleeping pad after every slide, adding an unwelcome workout to the whole nap situation.

Carbon Glacier Camp

While we are perched at our hill-side campsite, the wind continues to pick up all afternoon, until we are dealing with a full-blown gale coming up off of the Carbon glacier, blasting us with spindrift (loose snow) that is extremely effective at finding it’s way into any small opening in a jacket or sleeping bag breathing hole, and blowing away anything in camp that isn’t quite literally tied down, as Dan soon discovers as his foam sitting pad is sent flying across the glacier by a gust.

This afternoon, Dan and I both make the unfortunate but inevitable discovery that we must answer the call of nature, and get acquainted with the phenomenon of the dreaded "Blue Bag". Basically, on a heavily trafficked peak like Rainier, the National Park Service makes climbers pack out their own waste, and in order to do this, they provide climbers with small, durable blue plastic bags. I won't go into details, but suffice it to say that it is a new and not entirely pleasant experience for both of us. Enough said.

Sunlight on Ridge over Carbon Glacier

The wind gets stronger over the course of the afternoon, and we decide that it would be a bad idea to try and climb in these conditions, so we decide that instead of beginning our climb later that night, it would be smart to stay at this windy campsite, and get up early the next morning to start up the ridge. At some point late this evening, I am sitting in my sleeping bag but still freezing, so I decide that it’s time to get out and do something to warm up.

Sunset Over Carbon Glacier

It’s already past sunset, and it’s starting to get even colder out in addition to the already howling wind, but I get out of my sleeping bag, pile on the layers, and go to town building what was originally intended to be a very small, half-assed snow wall to block at least a tiny bit of the winds that are apparently trying to blow us off the mountain. More importantly, this alpine construction project is intended to serve as physical labor to warm me up and wear me out enough so that when I get back into my sleeping bag, I will actually be warm enough and tired enough to fall asleep, downhill slippage be damned. After an hour and a half of grunting, swearing, excavating, hauling, hands-on lessons in snow physics, and surprisingly hard work, I end up completing a semi-respectable 12 foot long, 3 foot high wall of snow blocks, cemented together by the slightly wetter layer of snow that was consistently found 2 or 3 inches under the crusty surface layer that made great blocks after some patient and careful quarrying. All this masonry work has achieved its desired purpose, so comfortably warm and vaguely weary, I slither back into the slippery confines of the sleeping bag, and head off into a surprisingly decent night’s sleep.